How racist policing took over American cities, explained by a historian- 2

How racist policing took over American cities, explained by a historian - 2

The effect of that is to produce yet another battery of crime statistics coming out of northern cities that shows high rates of arrest of black people during the Prohibition period, when in fact, they’re being targeted for political clampdowns of overwhelmingly white underground activity. It’s just remarkable.

The effect of that is to produce yet another battery of crime statistics coming out of northern cities that shows high rates of arrest of black people during the Prohibition period, when in fact, they’re being targeted for political clampdowns of overwhelmingly white underground activity. It’s just remarkable.

And yet again, the white public doesn’t read any footnotes or get any asterisks to it. What they get is evidence of disproportionate numbers of arrests in the black community during a time where just about everybody knew who was behind bootlegging.

[But] black people — black reformers, black activists, black scholars, black journalists — were always documenting what was happening to them. They were always resisting and they made some headway, beginning in the 1920s, around calling attention to systemic police racism and discrimination.

Anna North:That’s the next thing I wanted to ask about. I know that you wrote about this a little bit in your Washington Post op-ed last year — talk to me a little bit about the history of protests against racist policing.

a group of people standing in front of a crowd: Protesters clash with police during a rally against the death of Minneapolis, Minnesota man George Floyd at the hands of police on May 28, 2020 in Union Square in New York City. Floyd's death was captured in video that went viral of the incident. Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz called in the National Guard today as looting broke out in St. Paul.Khalil MuhammadThe earliest days of the civil rights movement were focused on the problem of lynching.

The NAACP literally begins because of lynching. And [one] reason was because of the threat of lynching in the North. It’s not to say that the progressives who founded the organization in 1910 didn’t care about lynching that had been going on in the South. But it was kind of like a George Floyd moment. It was like, “Holy smokes, if this can happen in Springfield, Illinois, where a lynching had occurred in 1909, then we’ve got to draw a line in the sand.”

Alongside their focus on racial violence in the earliest days, they also began to pay attention to police violence, particularly in the North, because the NAACP leadership was in northern cities. It was headquartered in New York. And so what was happening in their own backyards was more like systemic police violence than lynch mobs. And that began the process, particularly for W.E.B. Du Bois, who establishes kind of a police blotter, or let’s call it a police-brutality blotter, and the primary magazine for the organization.

Ida B. Wells, who was also another founder of the NAACP, begins to organize around police violence and other forms of racial violence in those cities. African Americans themselves start to resist policing and call attention. Ministers, teachers, bricklayers — essentially what was the working and professional class of black America at the turn of the 20th century are very vocal, and they demand police reform. They demand accountability for criminal activity amongst the police and they don’t get any of it.

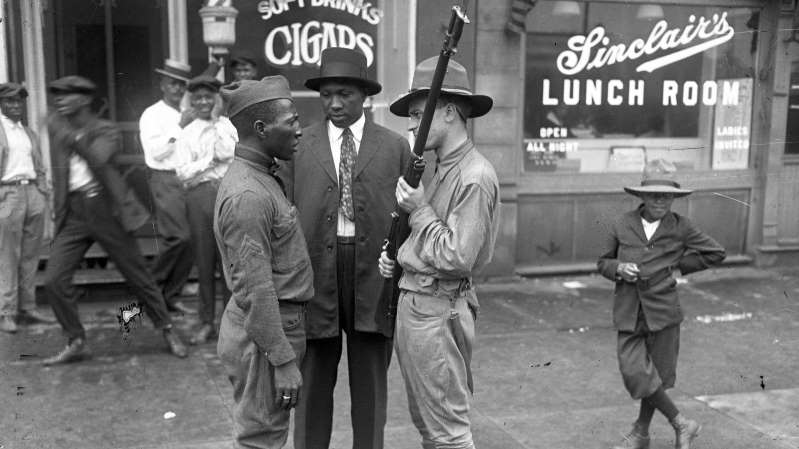

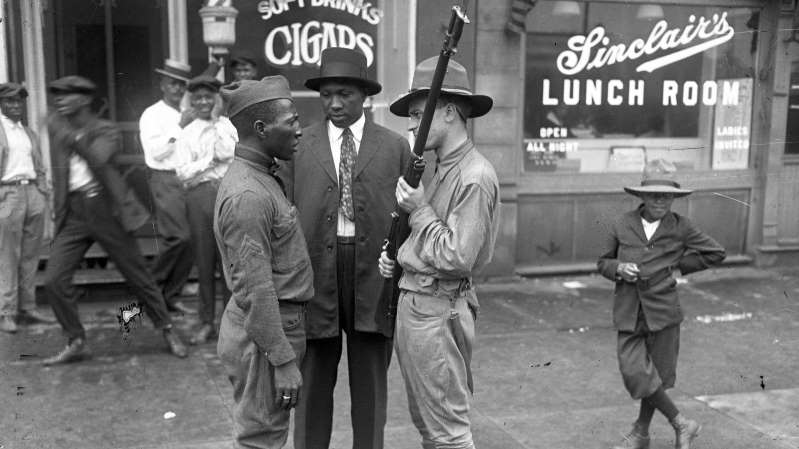

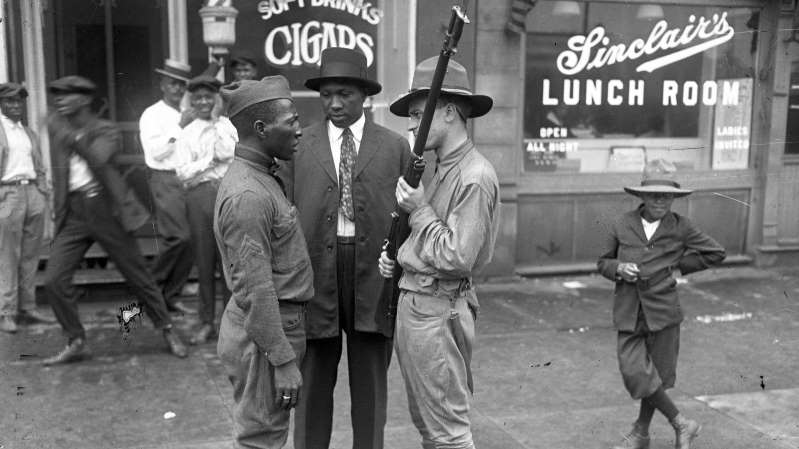

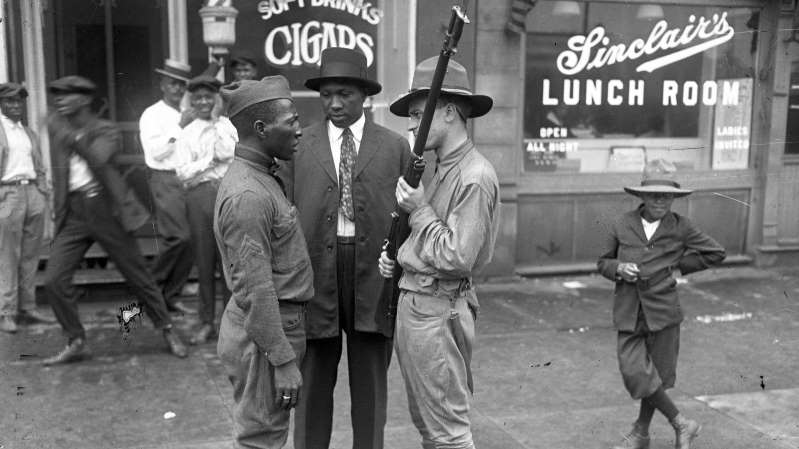

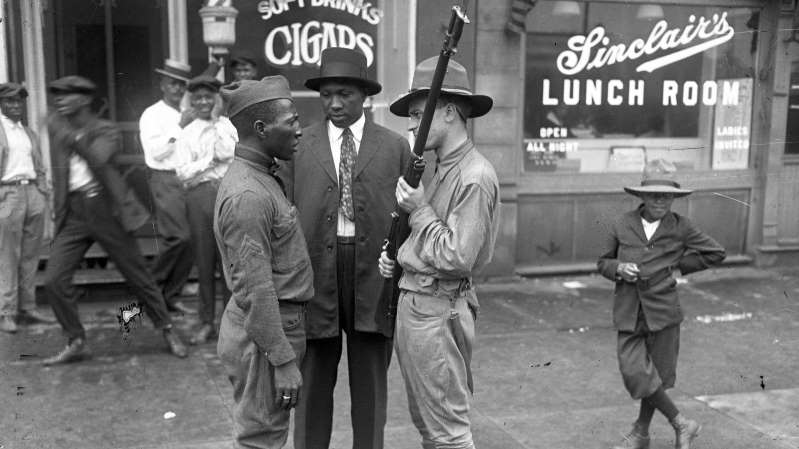

By the 1920s, the first of a series of race riots erupts in East St. Louis, spreads to Philadelphia. Another one occurs in Chicago. The Chicago one is sparked by the death of a [17-year-old] swimming in Lake Michigan who crosses an aqueous color line. Black people are outraged. They want justice. White people take offense and begin to attack them in their communities.

“The same basic idea that in white spaces, black people are presumptively suspect, is still playing out in America today”And what comes out of that is the first blue-ribbon commission to study the causes of riots. In that report, the Chicago commission [concludes] that there was systemic participation in mob violence by the police, and that when police officers had the choice to protect black people from white mob violence, they chose to either aid and abet white mobs or to disarm black people or to arrest them. And a number of people testify, all of whom are white criminal justice officials, that the police are systematically engaging in racial bias when they’re targeting black suspects, and more likely to arrest them and to book them on charges that they wouldn’t do for a white man.

People hold placards during an action on the Jaarbeursplein, in Utrecht, The Netherlands, on June 5, 2020, in solidarity with protests raging across the United States over the death of George Floyd, an unarmed black man who died during an arrest on May 25. (Photo by Remko DE WAAL / ANP / AFP) / Netherlands OUT (Photo by REMKO DE WAAL/ANP/AFP via Getty Images)People hold placards during an action on the Jaarbeursplein, in Utrecht, The Netherlands, on June 5, 2020, in solidarity with protests raging across the United States over the death of George Floyd, an unarmed black man who died during an arrest on May 25. (Photo by Remko DE WAAL / ANP / AFP) / Netherlands OUT (Photo by REMKO DE WAAL/ANP/AFP via Getty Images)This report in 1922 should have been the death of systemic police racism and discrimination in America. It wasn’t. Its recommendations were largely ignored.

And a decade later, Harlem breaks out into what is considered the first police riot, where African Americans believe that an Afro-Puerto Rican youth has been killed by the police. Turns out he hadn’t been, but the rumor that he had leads to a series of attacks directed towards white businesses in Harlem and against the police. And eventually, that uprising leads to the Harlem riot report in 1935.

That report comes to the same conclusion, notes there needs to be accountability for police that need to be charged and booked as criminals when they engage in criminal activity. They call for citizen review boards and an end to stop and frisk, which they name in the report. And Mayor [Fiorello] La Guardia, the mayor of New York, shelves it, doesn’t do anything with it, doesn’t even share [it] with the public.

The only reason it ever saw the light of day was because the black newspaper, the Amsterdam News, published it in serial form. And a similar report is produced in 1943, and another report in 1968. They essentially all keep repeating the same problem.

Anna North :Given the history of clear identification of this problem, is now any different? Are we seeing any shift in attitudes of white Americans toward the idea of black criminality? Will we see any changes come out of this moment?

ething different, I would say this: This moment is very helpful when it comes to taking on this question. The problem is that none of us can know how long this will last. None of us can know whether the simple charging of three other men and eventual conviction for all involved in the killing of George Floyd will be the answer people were looking for who are newcomers to this.

But I can tell you that a lot of the activists and movement leaders, the organizers, academics like myself, know that this has never been a problem about one, two, three, or four officers who unjustly kill an unarmed, innocent black person — and I say innocent because George Floyd had not been convicted of anything. We know that this has never been about that.

The problem is the way policing was built and what it’s empowered to do, which is — to put it in terms that are resonant in this moment — they’ve been policing the essential workers of America. And the fact that black people over index as the essential workers of America, when in fact, that was what their presence here was meant to be about: to provide the labor to build wealth in America, and then the only form of freedom that they really ever had, which was the freedom to work for mostly white people.

In this pandemic moment, I think we’re able to see more clearly that the very people we’re willing to sacrifice the civil rights and civil liberties of are the very people we also depend upon to keep our utilities running and our groceries coming into our homes. What this moment leads us to is a crossroads for most newcomers to define justice beyond an individual case or even cases, but to define justice as a form of limiting what police officers have been able to do, which is to protect white privileges in America.

Some people call that defunding the police. Some people call it abolition. But what it all means is that there should be less policing of black America and more investment in the [socioeconomic] infrastructure of black communities. And police officers are not the people to do that work.

Reference: Vox: Anna North June 5th 2020

Articles-Popular

- Main

- Contact Us

- Planetary Existences-2

- Planetary Existences

- TWO REVELATIONS-2

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 9

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 8

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 10

- The Two Revelations

- The Fourth Way - Study of Oneself - P.D.Ouspensky

- Impeachment Investigators Subpoena White House - Ukraine

- Universality of Initiation

- Initiation and the Devas

- The Path Of Initiation

- The Participants In The Mysteries-2

- The Fourth Way - Wrong Functions - P.D Ouspensky

- The Final Initiation

- Statues are a mark of honour. Like Edward Colston, Cecil Rhodes and Oliver Cromwell have to go

- Discipleship - Group Relations - 2

- The Probationary Path - 2

- The Participants In The Mysteries

- Discipleship - Group Relationships

- Discipleship

- The Succeeding Two Initiations

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 7

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 6

Articles - Latest

- They Lied to Us! The Truth They Hid About Hitler’s Death — Gerard Williams

- Ramaposa Dragged Out of Parliament

- Madagascar Goverment Collapse

- The Reality of Digital Id

- Welcome To The End Of Western Dominance

- Why is the Sahel turning its back on France?

- Sarkozy gets 5 years in prison in Gadhafi case

- The EU in 2025: A union at the crossroads of chaos

- Deep distrust of EU leaves Italy's Meloni in a corner over bailout fund

- Regime crisis in France: Bayrou falls, now Macron must go!

- Idi Amin president of Uganda

- Anger at Starmer's 'surrender deal' that hands Spain control over Gibraltar border

- Iran doubles down as US signals Israel could strike during nuclear talks

- What could have caused Air India plane to crash in 30 seconds?

- WW3 fears explode as Britain now Russia's 'enemy number 1' - even ahead of Ukraine