How racist policing took over American cities, explained by a historian

How racist policing took over American cities, explained by a historian

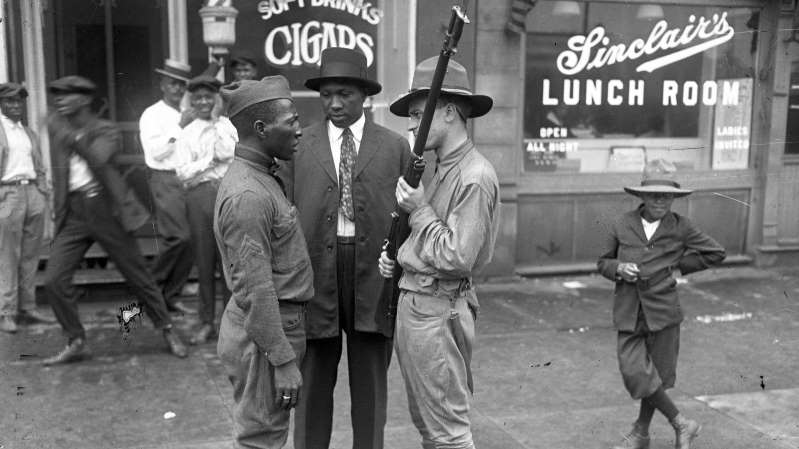

Editor’s note: The opinions in this article are the author’s, as published by our content partner, and do not represent the views of MSN or Microsoft.Editor’s note: The opinions in this article are the author’s, as published by our content partner, and do not represent the views of MSN or Microsoft.Eugene Williams, a 17-year-old black boy, was stoned to death by white people in 1919 after he swam into what they deemed the wrong part of Lake Michigan.

In response, black people in Chicago rose up in protest, and white people attacked them. More than 500 people were injured and 38 were killed. Afterward, the city convened a commission to study the causes of the violence.

The commission found “systemic participation in mob violence by the police,” Khalil Muhammad, a professor of history, race, and public policy at Harvard Kennedy School and author of the book The Condemnation of Blackness: Race, Crime, and the Making of Modern Urban America, told Vox.

“When police officers had the choice to protect black people from white mob violence, they chose to either aid and abet white mobs or to disarm black people or to arrest them.”In the process of compiling the report, white experts also testified that “the police are systematically engaging in racial bias when they’re targeting black suspects,” Muhammad said. The report “should have been the death of systemic police racism and discrimination in America.”

That was in 1922.That was in 1922.

It’s almost 100 years later, and thousands of Americans are in the streets daily, protesting the same violence and racism that the Chicago commission documented. It may seem like nothing can change, but Muhammad said the last several weeks could be a wake-up call for some Americans to what policing in this country really means.

Part of that awakening, though, also involves understanding the history of police violence. Muhammad’s work focuses on systemic racism and criminal justice; The Condemnation of Blackness deals with the idea of black criminality, which he defines as the process by which “people are assigned the label of criminal, whether they are guilty or not.”

That process has been a vicious cycle in American history, Muhammad explains, wherein black people were arrested to prevent them from exercising their rights, then deemed dangerous because of their high arrest rates, which deprived them of their rights even further.

I spoke with Muhammad by phone to better understand this history, what it means today, and what it would take to make 2020 and beyond different from 1922. A transcript of our conversation, lightly edited for length and clarity, follows.

Anna North Can you trace how the idea of black criminality appeared in America, starting with slavery?

Khalil MuhammadThe notion of criminality in the broadest sense has to do with slave rebellions and uprisings, the effort of black people to challenge their oppression in the context of slavery. Slave patrols were established to maintain, through violence and the threat of violence, the submission of enslaved people. But we really don’t get notions of black criminality in the way that we think of them today until after slavery in 1865.

The deliberate choice to abolish slavery, [except as] punishment for crime, leaves a gigantic loophole that the South attempts to leverage in the earliest days of freedom. What that amounts to is that all expressions of black freedom, political rights, economic rights, and social rights were then subject to criminal sanction. Whites could accuse black people who wanted to vote of being criminals. People who wanted to negotiate fair labor contracts could be defined as criminals. And the only thing that wasn’t criminalized was the submission to a white landowner to work on their land.

People hold up signs during a protest outside of City Hall against racial inequality in the aftermath of the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd in Los Angeles, California, U.S. on June 6, 2020.

REUTERS/Patrick T. Fallon© Thomson Reuters People hold up signs during a protest outside of City Hall against racial inequality in the aftermath of the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd in Los Angeles, California, U.S. on June 6, 2020. REUTERS/Patrick T. FallonShortly afterwards, a lot of the South builds up a pretty robust carceral machinery and begins to sell black labor to private contractors to help pay for all of this.

And for the next 70 years, the system is pretty much a criminal justice system that runs alongside a political economy that is thoroughly racist and white supremacist. And so we don’t get the era of mass incarceration in the South, what we get is the era of mass criminalization. Because the point is not to put people in prison, the point is to keep them working in a subordinate way, so that they can be exploited.

Anna North :What was happening in the North while this mass criminalization was happening in the South?

Khalil Muhammad

There had already been African Americans [in the North] before the end of slavery, and they were subjected to forms of segregation. But it wasn’t really until the beginning of the 20th century, when streams of black migrants began to move to northern cities, and particularly during World War I and what became known as the Great Migration, that we began to see the increased ascription of black people as prone to criminality, as a dangerous race, as a way of essentially limiting their access to the full fruits of their freedom in the North.

Social science played a huge role. What we’d call today “academic experts” of one kind or another, were part of the effort to define black people as a particular criminal class in the American population. And what they essentially did was they used the evidence coming out of the South, beginning in the first decades after slavery. They used the census data to point to the disproportionate incarceration of African Americans. They were almost three times overrepresented in the 1890 census in southern prisons.

So that evidence became part of a national discussion that essentially said, “Well, now that black people have their freedom, what are they doing with it? They’re committing crimes. In the South and in the North, and the census data is the proof.” And so people began to build on that data and add to it. Police statistics began to become more important in determining how black people were doing, whether they were behaving or not. We quickly moved from census data to local data, from South to North, and we begin to see the consolidation of a set of facts that black people have a crime problem.

Anna North: So it’s a cycle:

Black people were incarcerated in the South, and because they were incarcerated, this whole theory that black people were criminal was built on top of that?

Khalil Muhammad

Demonstrators hold up signs at the "Black Lives Matter Plaza", near the White House, during a protest against racial inequality in the aftermath of the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd, in Washington, U.S. June 6, 2020. REUTERS/Jim Bourg© Thomson Reuters Demonstrators hold up signs at the "Black Lives Matter Plaza", near the White House, during a protest against racial inequality in the aftermath of the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd, in Washington, U.S. June 6, 2020. REUTERS/Jim BourgThat’s exactly what I’m saying. Of course, there’s no footnotes or asterisks to what was happening in the South. People just take the data at face value, kind of like people take the data at face value today. They just look at the data and say, “Oh, well of course, look what’s happening in these communities.”

Anna North: How do we see these attitudes about black criminality play out in policing around the country, leading up through the 20th century to the present?

“When police officers had the choice to protect black people from white mob violence, they chose to either aid and abet white mobs or to disarm black people or to arrest them”Khalil Muhammad Once we have the consolidation of the fact that crime statistics prove nationally, everywhere, that black people have a crime problem, the arguments for diminishing their equal citizenship rights are national. They’re not just southern any longer. And they’re at every level of society — local, state, federal.

They are existing in cultural products like The Birth of a Nation, the first truly major Hollywood film release. Black criminality becomes the most dominant basis for justifying segregation, whether legal or by custom, everywhere in America.

It had already defined the heart of the Jim Crow form of segregation, but it really begins in the Great Migration period to shape the maldistribution of public goods for black people — access to neighborhoods, access to schools, access to hospitals, access to forms of leisure. And, of course, all of these restrictions are enforced by white citizens but most especially by local law enforcement, by police officers.

In the South, police were less on the front lines because there were fewer of them. There was more vigilante enforcement of white supremacy: A white man really could shoot a black man or woman down in the middle of the street and get away with it. That was less likely to happen in the North — what was more likely to happen was for a white resident to simply call the police.In the South, police were less on the front lines because there were fewer of them.

There was more vigilante enforcement of white supremacy: A white man really could shoot a black man or woman down in the middle of the street and get away with it. That was less likely to happen in the North — what was more likely to happen was for a white resident to simply call the police.

The same basic idea that in white spaces, black people are presumptively suspect, is still playing out in America today. The idea that police officers should prevent crime in black communities, rather than simply policing the borders of black communities, is what gave us stop and frisk, which actually is not just from the 1990s or inspired by “broken windows” policing, but versions of it were playing out very officially in the 1960s. And by looking at the archives, which I’ve done in my book, unofficially and unnamed, going back to the 1910s and ‘20s.

Demonstrators march with placards along Pennsylvania Ave, during a protest against racial inequality in the aftermath of the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd, in Washington, U.S. June 6, 2020.

REUTERS/Erin Scott© Thomson Reuters Demonstrators march with placards along Pennsylvania Ave, during a protest against racial inequality in the aftermath of the death in Minneapolis police custody of George Floyd, in Washington, U.S. June 6, 2020.

While that pattern played out, one of the things that happens during Prohibition is that the manufacturing and distribution of alcohol creates this massive underground economy, which is now being regulated by white ethnic men who don’t sue each other in civil court, but actually shoot at each other when they’re competing over the spoils of bootlegging.

And a lot of that action is deliberately put in black communities.While that pattern played out, one of the things that happens during Prohibition is that the manufacturing and distribution of alcohol creates this massive underground economy, which is now being regulated by white ethnic men who don’t sue each other in civil court, but actually shoot at each other when they’re competing over the spoils of bootlegging.

And a lot of that action is deliberately put in black communities. The speakeasies, the corruption is hidden within black communities. Everyone is complicit in this: The bootleggers are complicit, the police are complicit. The only people who aren’t complicit are everyday working-class black people who don’t want what’s happening in their communities to be happening.

Reference: Vox: Anna North June 5th 2020

Articles-Popular

- Main

- Contact Us

- Planetary Existences-2

- Planetary Existences

- TWO REVELATIONS-2

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 9

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 8

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 10

- The Two Revelations

- The Fourth Way - Study of Oneself - P.D.Ouspensky

- Impeachment Investigators Subpoena White House - Ukraine

- Universality of Initiation

- Initiation and the Devas

- The Path Of Initiation

- The Participants In The Mysteries-2

- The Fourth Way - Wrong Functions - P.D Ouspensky

- The Final Initiation

- Statues are a mark of honour. Like Edward Colston, Cecil Rhodes and Oliver Cromwell have to go

- Discipleship - Group Relations - 2

- The Probationary Path - 2

- The Participants In The Mysteries

- Discipleship - Group Relationships

- Discipleship

- The Succeeding Two Initiations

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 7

- Jeffery Epstein - The Saga - 6

Articles - Latest

- They Lied to Us! The Truth They Hid About Hitler’s Death — Gerard Williams

- Ramaposa Dragged Out of Parliament

- Madagascar Goverment Collapse

- The Reality of Digital Id

- Welcome To The End Of Western Dominance

- Why is the Sahel turning its back on France?

- Sarkozy gets 5 years in prison in Gadhafi case

- The EU in 2025: A union at the crossroads of chaos

- Deep distrust of EU leaves Italy's Meloni in a corner over bailout fund

- Regime crisis in France: Bayrou falls, now Macron must go!

- Idi Amin president of Uganda

- Anger at Starmer's 'surrender deal' that hands Spain control over Gibraltar border

- Iran doubles down as US signals Israel could strike during nuclear talks

- What could have caused Air India plane to crash in 30 seconds?

- WW3 fears explode as Britain now Russia's 'enemy number 1' - even ahead of Ukraine